Votre navigateur ou la version de votre navigateur n’est pas adapté pour ce site.

Pour une utilisation optimale du site, veuillez faire une mise à jour de votre navigateur en cliquant sur ce lien

Explanation of the Court of Cassation decision from the 20th of May 2020 (Civ. 1ère, 20th of May 2020, n° 19-12278)

As the wine sector is deeply impacted by the consequences of the current worldwide health crisis and by the customs laws on wines exported to the USA, and as the overall alcohol consumption is significantly decreasing in Europe, it is now affected by a case law in relation to advertisement.

The French Court of Cassation just settled a dispute regarding the Evin Law from January, 10th 1991 by a decision made on May 20th 2020.

As a reminder, this law forbids the overall advertisement of alcoholic drinks and tobacco. The Public Health Code, however, authorises some forms of advertising (such as radio, signs, internet…) under specific conditions, while also listing authorised contents. It is precisely on this aspect that the High Jurisdiction recently adjudicated. It interprets article L. 3323-4 of the Public Health Code – which lists contents authorised to be advertised – as such:

“Authorised advertisement for alcoholic drinks is limited to indicating the degree of alcohol, of the origin, of the denomination, of the product’s composition, of the name and of the manufacturer, depositaries and agents’ adress as well the production process, the selling modalities and of the way to consume the product.

The advertisement can contain references to production regions, prices and distinctions received, designation origins […] to geographic indications […]. It can also refer objectively to colours and olfactory and taste qualities of the product”

This decision was published in the Bulletin, showing the importance that the Court of Cassation wishes to give it.

Let’s briefly recap facts. The case started in 2015, when the Association Nationale de Prévention en Alcoologie et Addictologie (the National Organisation for the Prevention of Alcoholism and Addiction) sued the Kronenbourg company (who carries Grimbergen beers). This organisation was asking the interdiction of two movies (“The Legend of the Phoenix” and “Territories of a Legend”, a game (“The Territories Game”) as well as of an ad slogan (“The intensity of a legend”).

The overall marketing campaign was evolving around a mythical creature (the Phoenix), which was supposed to be the perfect analogy of the legendary origin of the Grimbergen beers.

It is on this precise aspect that the Evin law’s dispositions come into play. The Judicial Tribunal of Paris and the Paris Court of Appeal had different views of the article L. 3323-4 of the Public Health Code.

The Court of Appeal considered that the origin of the product could be presented in a hyperbolic fashion and that only the mentions concerning the colours and olfactory and taste qualities of the products had to be purely objective. Moreover, it also added that only the incitation to consume alcohol in excess was against the public health goals as set by the law.

So what was at stake in this case depended on the reply to the following question: does the objective nature explicitly presented for the elements related to the colours and the olfactory and taste qualities of a product also applies to other elements of advertisements accepted by the L. 3323-4 of the Public Health Code (such as references to the production region, geographical indications…)?

The Court of Cassation considers that promoting alcoholic drinks must imperatively be objective, informative and in no way hyperbolic as in the presented case. The Court also indicates that this analysis touches the entire advertising content and not just references to the coulours and olfactive and taste qualities of the product.

This interpretation of article L. 3323-4 appears quite large, and could even be seen as contradictory to the text.

In any case, in order to better understand this decision, it is important to remember the existing jurisprudence.

Since the Evin Law was implemented, the jurisprudence was very severe towards the marketing campaigns that were submitted to it.

Two important decisions, on the 15th of May 2012 and 1st of July 2015, however took different turns. For the 2015 decision, a looser understanding of the Evin Law was chosen. The advertisement in question was in favour of the Professional Council of Bordeaux Wines, with professionals from the sector depicted, a glass in hand:

This ad was considered as fitting the legal requirements. The Court adopted a looser interpretation of the law and indicated that the joy coming from the images was not overstepping what was required in terms of promoting products and fitting the marketing process.

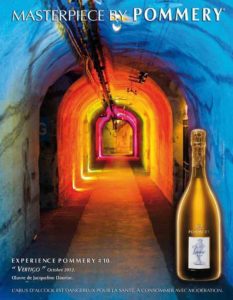

This jurisprudential wave was later confirmed, for example through a decision made by the Paris Court of Appeal on the 21st of December 2017. The art piece Vertigo, by Jacqueline Dauriac, had been reproduced in an advertisement for Pommery:

Even if the Paris Court of Appeal indicated that the attractive effect of the ad should stay within the realm of the informative indications and objective references, it also added that “the law does not forbid a figurative indication of the enunciated elements, nor the use of art for the authorised reference or indication”. The Paris Court of Appeal thus declared that the ad was lawful and made a distinction between the marketing message (that need to be objective) and the elements composing it (which can be figurative).

The GRIMBERGEN decision from the 20th of May 2020 does not fit into this (more) liberal jurisprudential wave and goes back to a more traditional, restrictive view on the Evin law requirements, which are unfavourable to marketing campaigns on alcoholic drinks.

This serves as a warning to the sector: elements that are part of the marketing content need to be strictly controlled and limited to purely objective and informative aspects, which do not limit themselves to the colours and olfactory and taste qualities of a product.

With this in mind, a marketing campaign containing subjective or figurative references, or referring to excess could be considered as illicit.